chainsawriot

Home | About | ArchiveA One-person Agenda for Open Review in Communication

Hi! My name is nobody and this is my take, which you can safely ignore, on the current Open Communication Science discussion. Having said so, my personal opinion does not represent any organization I am affiliated with.

As you may know, there are Open Science agenda, primer, practical road map, and layered framework specifically written for our field. We had a large (online) conference in 2020 with the theme being Open Science. There are also critical responses to the call for Open Science in an upcoming Journal of Communication special issue and these responses are about inclusiveness, colonial legacy, etc. I wonder, is Open Science really that controversial in our field? Now I know: It is.

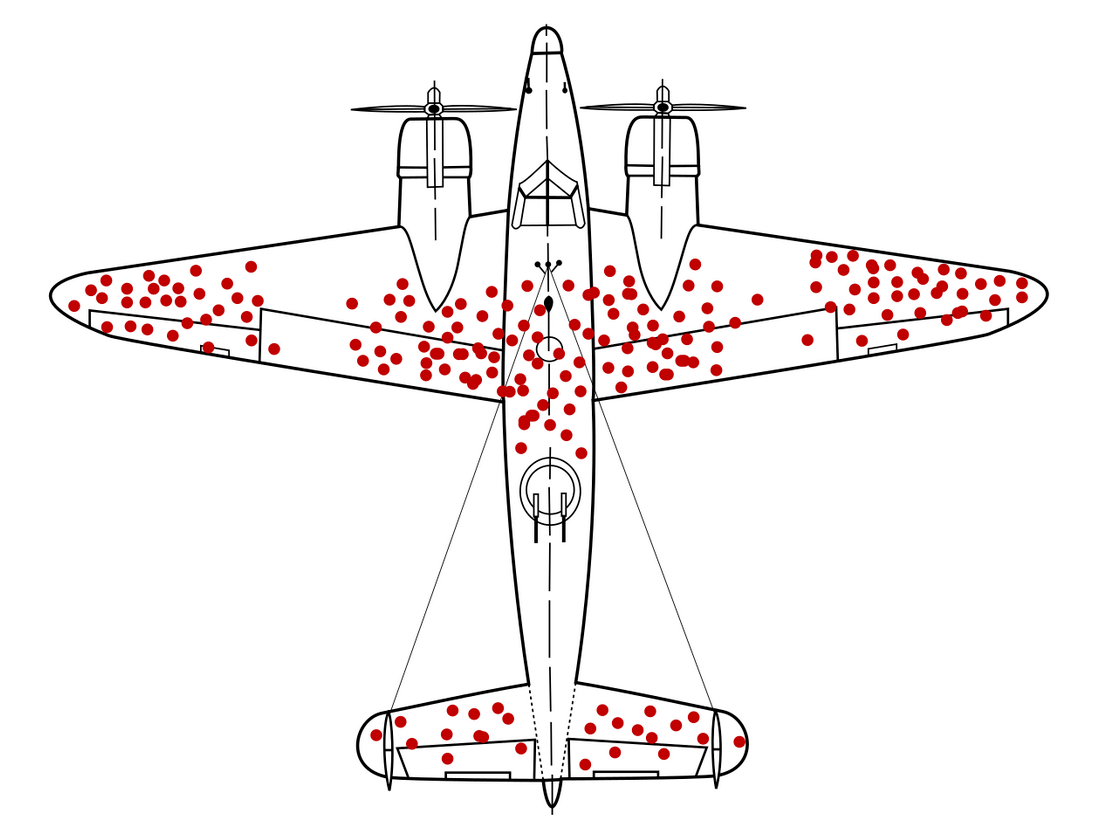

And then I have this imagery inside my head. The very famous image.

(Source)

(Source)

We let the Open Science fighter jets fly in the wild. And then some of them came back. It is nasty to say they have been “attacked”. Let me use a less aggressive, and context-appropriate term: some red dots have been added to indicate the weaknesses of the original call for Open Science. Those fighter jets “have been red-dotted”, if you like.

So, those jets came back with the following weaknesses being red-dotted: lack of inclusiveness, no protection of vulnerable populations, great potential for weaponization to serve political ends, power imbalance between social media companies and researchers, gamification of Open Science with those badges, distortion of scientific quality criteria, etc…

All of these are valid counterarguments and communication researchers need to think about how to at least mitigate these potential negative effects. Tobias Dienlin, for example, wrote an reflection on the “Open Science, Closed Door” essay (Fox et al. 2021). This kind of reflection is greatly appreciated.

However, if you know the original context of the jet image above, it’s about a study to answer the question of where should we add armor to those jets. A common response would be: let’s put armor onto the areas of those red dots. As it turns out, one should put even more armor to the areas without those red dots. Why? Because those jets that have been attacked in those areas won’t fly back. Wasted. The classic definition of surviorship bias.

I reflect myself: why is there an area of Open Science that have no been discussed at all by communication researchers? Using the plane analogy, could it be due to A: in the first place we have not put that area in the jets or; B: that area is so vigorously red-dotted and the jets with that area being red-dotted couldn’t fly back.

The area that I have in mind is Open Peer Review (or simply Open Review). But what exactly is Open Peer Review?

Open Peer Review: a pillar of Open Science

Open Review is one of the four pillars of Open Science: Open Data, Open Code / Methodology, Open (access) Paper and Open Review. The term, as many have defined, is actually an umbrella term. Broadly defined, it is about the process of making peer review more transparent. Practically, there are many traits. But what I want to bring to your attention the so-called BMJ model: Open Identities by default, Open Reports and Open Pre-review Manuscripts. 1 BMJ implemented the first version of this system in 1999 and then the system grows organically ever since. Before I move on, it is easy to be distracted by the controversial practice of Open Identities, a.k.a. unblinded peer review. It is true that scientists are still arguing the merits of unblinded peer review and it is easy then to wholesale disregard the entire notion of Open Review. Although I support the BMJ model, I am also, or more so, in favor of a slightly more restrictive model called Transparent Peer Review (BMJ Model minus Open Identities, i.e. making anonymized peer-review reports available).

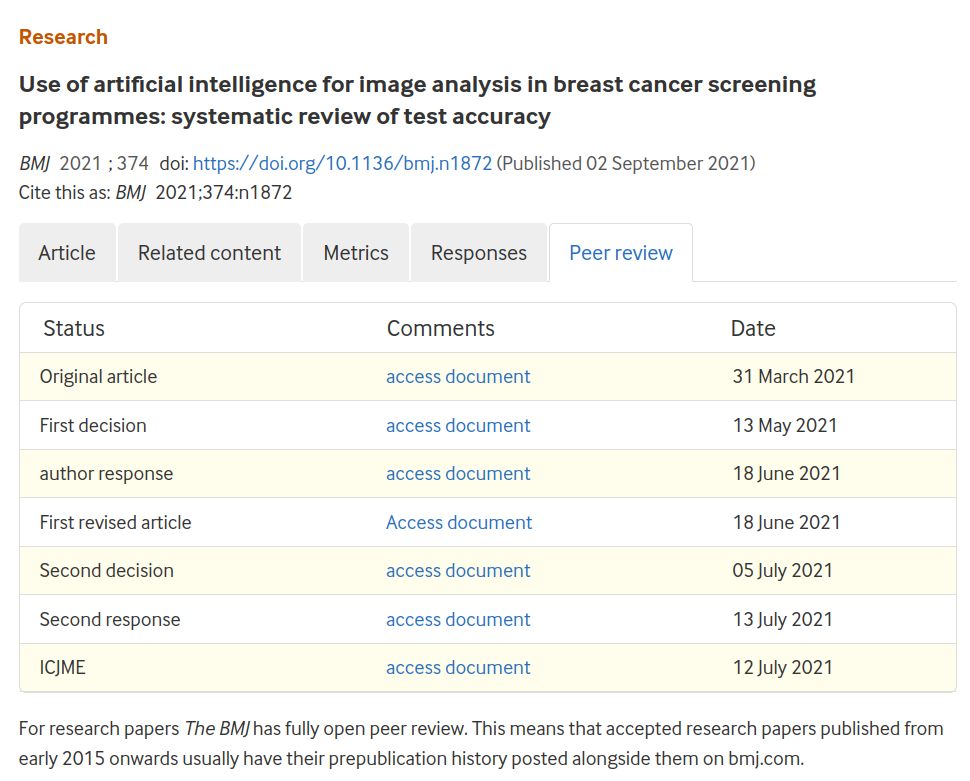

To see the BMJ model in action, you can just go to the BMJ website. Almost all new BMJ research articles have a section called “Peer Review”. Under this section, you can find the entire peer review history of the paper.

To me, these information is as important as openly available data and code. I argue that at least half of the opacity in modern scientific process lies in the publication process, specifically in the peer-review process.

If Open Data and Code are to improve reproducibility and replicability of science, we need Open Review to at least provide a transparent record of the intrinsically irreproducible and irreplicable peer-review process. Some people say Open Science distorts the quality criteria of science. I say Open Review shows us explicitly what the “quality criteria” they are actually referring to. Also, it shows how reviewers—they themselves are also scientists—hold these “quality criteria” when they do their peer reviews. Or are they relying on vague, subjective yardsticks such as “interesting”?

The quality of peer review can sometimes be extremely bad. Researchers, at some points, would have received the so-called “two-liner” (or even “one-liner”) reviews. These reviews are of extremely bad quality and usually have only two lines either saying the paper is very good or very bad, plus another line saying the English of the paper needs improvement. It is currently unknown how associate editors deal with these two-liner reviews. Suppose in a hypothetical situation, a very established researcher A, being busy or for whatever reasons, has given a two-liner review. Would the associate editor, who might be the student of researcher A, disregard the two-liner? Also, if there is a troll-like “reviewer 2”-style researcher B who has an agenda to shoot down a competitor’s submission (regardless of quality), is it possible to detect under the current opaque model? If a journal makes it clear to researcher A and researcher B that their reviews will be eventually open to the public, do you think they would commit those acts? At least, they would think clearly before accepting the peer review.

We also know there are potential (implicit) biases in the peer review process. The famous one in political communication is that studies from the Global North are context-free while those from the Global South always need contextualization. Taking it to an extreme, that’s “The American Universal versus the Idiosyncratic Other” (Boulianne, 2019). Of course, the well-known file drawer effect: reviewers and editors might shoot down a paper with negative results, despite the statistical power. As the peer review is opaque even after a paper is published and given the fact that top journals in the field are filled mostly with papers from the Global North and with positive results, how can we ensure these biases don’t exist? With no transparent record, no one knows.

Furthermore, peer review is “hackable”. Peer-review fraud is not uncommon. It has been shown that 33% of retracted articles are due to compromised peer review. Up to this day, some journals still mandate authors to suggest reviewers. For these journals, it is extremely easy to assign a friend or even create pseudonyms to review one owns papers. Apart from these obvious fakery, there are also other way for authors, reviewers and editors to soft-hack the system such as reviewer-coerced citation. It is also possible for authors to fake some very favorable results for passing the peer review and then modify the paper to the actual state after acceptance. These post-acceptance edits are usually not peer reviewed. That’s the reason why the complete history of the peer review, including the pre-review manuscripts, is important.

The alternative to (the current) peer review is not to abandon peer review, but to support a more transparent peer review system. Without such transparent peer review system, peer-review hacking reviewers and editors, “two-liner” researcher A, and “reviewer 2-style” researcher B are protected. Not reviewers who do honest work.

The curious (missing) case of Open Review

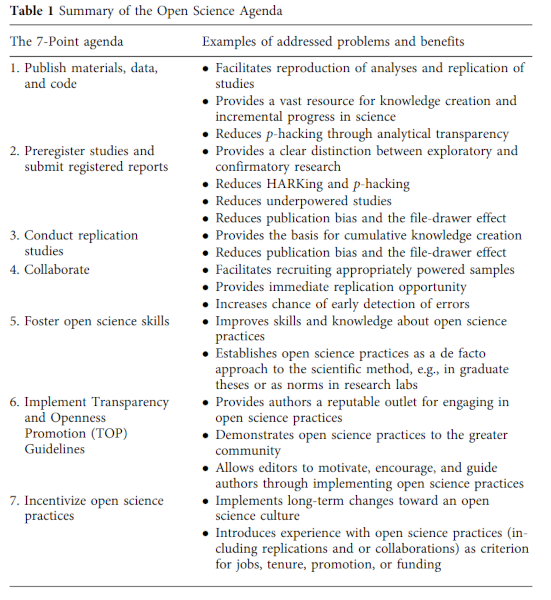

After this short introduction to Open Review, we can go back to the jet fighter and the two arguments. In our field, Open Review is curiously missing in the scholarly discourse about Open Science. The 7-point Agenda (Dienlin et al. 2021), for example, does not involve Open Review. Using the jet fighter imagery above, Open Review seems not even to be a part of the fighter jet in the first place.

(Source: Dienlin et al. 2021)

I can imagine why Open Review is not the current focus of Open Science. It is important to promote what we should do first. Shifting the focus to what journals should do might blur the focus. Historically, it is also harder for researchers to push journals to do what they should do: OA, allowing preprints, even retracting problematic papers. Some would even argue communication journals are actually doing very well by restating what they say in their instructions to authors.

But as this paper (Markowitz et al., 2021) points out, Open Science has been around in our field for over a decade now. I think it’s time to start the conversion about Open Review. Let the Open Review figther jets fly.

If Open Identities is controversial, communication journals could at least start considering Open Reports and Open Pre-review Manuscripts. Usually, these “new innovations” (if you consider something that has been in place in BMJ for over two decades as new) are adopted first by newer journals. For example, the OG Nature didn’t introduce Open Reports. But Nature Communications did. Only starting from February 2020 has the OG Nature started Open Reports.

As a field does not have any history in Open Review, I think established communication journals —together with new journals— should consider to adopt some traits of Open Review. Specifically, some Open Access by default and established communication journals should consider Open Review. The names I have in mind are Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, International Journal of Communication and Social Media + Society. Conferences such as ICA have an even greater incentive to adopt Open Review.

Postscript: the Q & A

Q: Authors might identify reviewers who criticized their papers through Open Review and seek revenge.

A: Yes. So I said upfront Open Identities is controversial. So, if there is concern about Open Identities, then just don’t do it. Even anonymized Open Reports could expose someone. BMJ, for example, has a mechanism for not opening review reports:

In rare instances we determine after careful consideration that we should not make certain portions of the prepublication record publicly available. For example, in cases of stigmatized illnesses we seek to protect the confidentiality of reviewers who have these illnesses. In other instances there may be legal or regulatory considerations that make it inadvisable or impermissible to make available certain parts of the prepublication record.

Like all other aspects of Open Science, protecting marginalized, vulnerable populations always take precedence over being transparent. Like BMJ, there must be a mechanism to not making the prepublication record publicly available.

Q: Without anonymity, reviewers might prove bland review, rather than critical review.

A: Once again, this problem of Open Review can be greatly mitigated by not adopting Open Identities.

Q: Open Review has been shown to reduce peer review participation.

A: True. Therefore, I think established communication journals should adopt Open Review first. It is very common for communication researchers to state in their CV that they did peer review for established journals. I believe the pull factor of reviewing for an established communication journal is way stronger than the push factor of reviewing for an Open Review journal.

Q: Open Review Journals usually only display the peer review record of accepted articles. We will know nothing about rejected articles. It is not a complete record.

A: True. Apart from the BMJ model, there is also the JMIR’s Open Community Peer Review model, therein submissions are by default uploaded to a preprint server and reviewers are then crowdsourced. In such a system, rejected articles are also having an open record of peer review. I think as a meaning first step, BMJ model is easier to implement.

Q: How to implement Open Review? The publisher of my communication journal/conference website does not support it.

A: I believe the easiest way to implement Open Review (at least Open Reports) is to upload reviewer reports and author responses to OSF, Zenodo or Harvard Dataverse. Doing so also generates citable DOIs. On Harvard Dataverse, journal dataverses can be used for such purpose.

Q: I am still not convinced. But what can my communication journal do to improve transparency of peer review?

A: Schade. Here are things you can do:

- If your journal still mandates authors to suggest reviewers: STOP that!

- Make peer-view policy as explicit as possible: how to deal with bad peer reviews?

- Experiment with Open Review like BMJ did. Form your own opinion.

-

Actually, BMJ also has a post-publication peer review system called Rapid Response. ↩